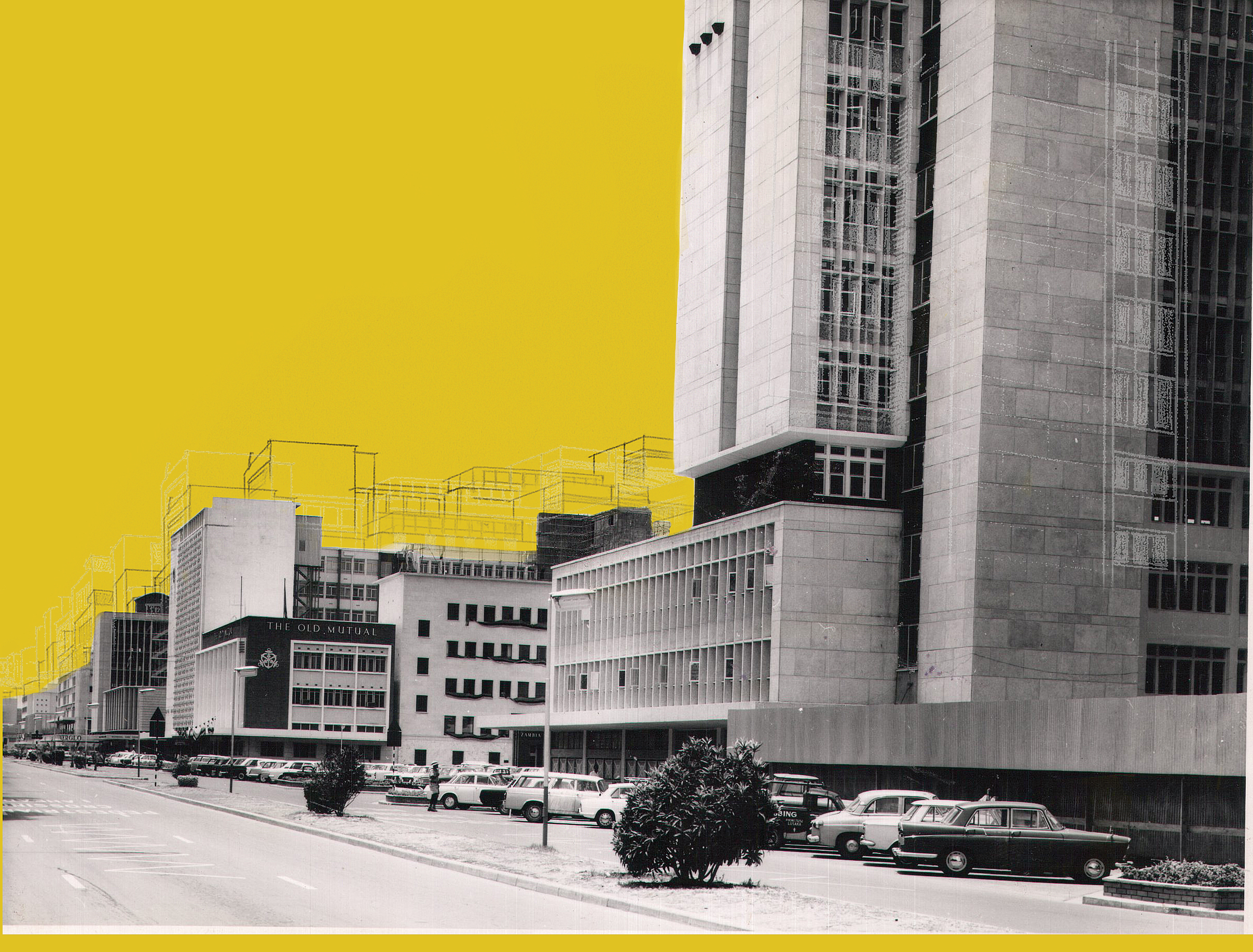

There was a time when Zambia not only imported cars, but also built them. In the glow of post-independence ambition, factories in Livingstone and the Copperbelt hummed with the sounds of assembly lines piecing together Peugeots, Toyota Hilux pickups, and Scania trucks. Imagine the pride: vehicles made by Zambian hands, rolling onto Zambian roads for the first time. This wasn't just industrial policy—it was a declaration that a young nation could manufacture its own future.

Post-independence Zambia embodied national ambition, channelling lessons from early industrialisation into bold initiatives uniquely tailored to Zambian circumstances. This drive was visible in local car assembly—a symbol of a nation daring to build and innovate. These formative years of making and sustaining industries remain relevant today because they show Zambia’s potential for self-driven development and the possibility of reclaiming that spirit.

Zambian Vehicle Assembly History

Vehicle assembly became one of the era’s most striking industrial experiments. Livingstone Motor Assemblers assembled Peugeot models and other small cars, while heavy vehicle operators brought Scania and Leyland designs to local roads. On the Copperbelt, plants assembled light-duty pickups and utility vehicles, including the early Toyota Hilux, in partnership with local manufacturers during the 1980s. These ventures emerged from the nation's incentives, joint ventures with foreign manufacturers, and favourable market conditions for local assembly. The result extended far beyond cars rolling off production lines—it created an ecosystem of technicians, trainees, and vehicle bodybuilders that sustained garages and component workshops across the country.

The First Zambian-Made Cars

I often imagine the moment when the first locally assembled car rolled out of the factory, its tyres touching Zambian soil for the first time. I imagine the patriotic pride Zambians must have felt, knowing that a vehicle crafted in part by Zambian hands could now travel through Zambian towns. It was a reflection of how the country saw itself at the time, daring to dream industrially.

Why Zambia's Car Assembly Industry Made Economic Sense

For a while, the model made practical sense—import substitution policies aimed to conserve scarce foreign exchange while creating jobs and building technical skills. Assembly plants, though dependent on imported kits, provided scaffolding for industrial capability. This phase offered essential experience and tested the viability of a truly local manufacturing base.

The Collapse of Zambia's Auto Industry

That fragile base is also why the collapse that followed was, sadly, predictable. Global oil shocks and chronic foreign exchange shortages during the 1970s and 1980s raised the cost of importing complete knock-down kits and replacement parts. Soon, plants were running below capacity, and maintenance began to lag. As time progressed, structural adjustment and trade liberalisation in the late 1980s and early 1990s removed many of the protections that had sheltered assembly. Cheaper fully built imports and a flood of second-hand vehicles undercut demand for locally assembled cars. The consequence was factory closures, idle machinery, and a fading hum where innovation once lived.

The Legacy of Livingstone Motor Assemblers

Lengthy receivership and court records of Livingstone Motor Assemblers reveal how quickly firm-level distress became a national concern—assets tied up, creditors waiting, and workers left to start over. Towns that once buzzed with body shops and spare parts merchants grew quieter. The loss wasn’t just economic; it was emotional, a slow fading of a collective belief that Zambia could build its own future with its own hands.

Can Zambia Revive Its Car Manufacturing Industry?

Can Zambia revive vehicle assembly? Today’s industrial environment is transforming, meaning any new attempt must adapt accordingly. Debate centres not on restoring old assembly lines, but on developing targeted sectors—such as components for electric transport or exports to regional markets. Local expertise and entrepreneurial momentum suggest ambition persists, but a sustainable revival requires deeper local sourcing, stable inputs, clear policy, and consistent markets. The lesson: acknowledge past limits, but focus revival on realistic, scalable goals.

When I think back to the whir of assembly halls, skilled workmanship being developed, and the pride of that first car driving out into the sun, I feel a deep nostalgia. The era was imperfect and under-resourced, but it taught Zambia lasting lessons: build the supply chain, secure parts and finance, and connect production to regional markets. If we choose to try again, let us do so with those lessons in hand. We can honour the pride of the past while shaping an industrial future that is resilient, confident, and, this time, built to last.