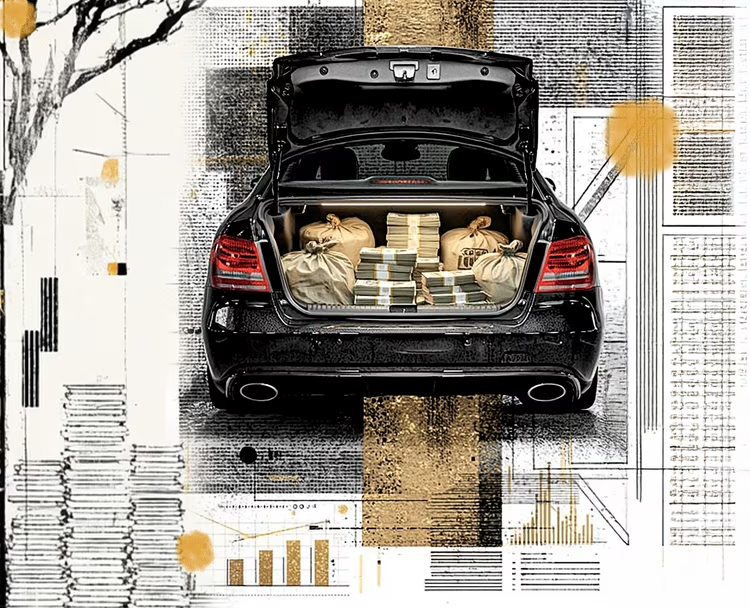

Zambia's most infamous bank heists aren't the Hollywood thrillers you'd expect. There are no elaborate tunnel systems or synchronised watches. Instead, these are stories of breathtaking audacity, inside knowledge, and in one case, a distraction involving cold meat. From a constable who weaponised his uniform to a poet with two MBAs who vanished with $400,000, these crimes reveal a pattern more disturbing than any action movie: sometimes the biggest threat comes from the inside.

To parrot a phrase that has been touted in after-school specials and school assembly halls, “crime does not pay”. It is a high-risk, low-return investment that leaves a trail of wreckage in its wake, and in no way is it glamorous. But it sure can be fascinating. Below is a list of Zambia’s most daring, disastrous, and downright unbelievable bank heists.

Zambian Police Officer Steals K622,483 in Armed Bank Robbery

If you were in a bank being robbed, your first instinct would probably be to call the police. But what happens when a police officer is the one committing the robbery? Constable Emmanuel Tembo figured out that among the perks of being a member of the Zambian Police’s protection unit, along with the job security and pension plan, comes the perfect diversion for a crime.

Under the guise of performing official duties, Tembo entered the Civic Centre branch of ZANACO in mid-September, armed with an AK-47 loaded with 30 rounds of ammunition and a plan. After the bank had ceased operations for the day, and employees were counting up and preparing cash to be transported, Tembo used his status to access the room, grabbed a sealed bag containing approximately K622,483 and fled.

Surprisingly, despite him being heavily armed, both security and other staff attempted to apprehend Tembo when they realised what was happening, but he slipped through their fingers and out of the city. The only clue as to which direction he fled is a package he left with a taxi driver in Shimabala containing his gun and police uniform. Notably absent, however, was the cash.

As of October 2025, Tembo has still managed to evade capture and is considered a wanted man. The search has intensified and seems to be as much a matter of combating crime for the Zambian Police Force as it is repairing their fractured pride. In the words of Police Public Relations Officer Rae Hamoonga, “We wish to make it categorically clear that this act of criminality will not go unpunished. Constable Emmanuel Tembo is now a fugitive, and the Zambia Police will relentlessly pursue him to ensure he answers for this crime”.

How Pamela Gondwe Stole $400K

On the lists of Zambian criminals, Pamela Gondwe has reached a rank of infamy attained by very few. Armed only with red lipstick, a cold sausage, and a cursive tattoo that says kindness on her chest, Gondwe made her way onto Interpol's Red Alert List of Most Wanted Criminals.

At 38, Gondwe held two MBAs, had a successful career at Barclays Bank, and was the author of an anthology of poems entitled Tears in a Suitcase, but when she fled with $400 000 dollars worth of cash in a bag, she added another tier to her CV, that of a wanted criminal.

As Branch Retail Support at the Barclays Long Acres branch, Gondwe was trusted with access to the bank vault. One September day, she arrived at work with a new empty bag, which she claimed she had bought that morning on her way to work. Leaving the bag in the vault room, she told a co-worker that she had received instructions from head office to record the serial numbers of all US dollars in the vault. As they began recording, Gondwe pulled out a sausage and offered it to her co-worker. The sausage was cold, and the co-worker headed to the staff canteen to warm it up and eat. When she returned, Gondwe said she had completed her task and was going to the salon to touch up her hair.

Pamela’s colleague did not get a chance to see her new hairstyle; in fact, she did not get the chance to see Pamela again. Gondwe had made off with $400 000 in cash in the empty bag she had “bought” that morning. When she took suspiciously long to return from her salon appointment, CCTV footage revealed her stuffing the money into a bag and using the back door of the bank to leave.

Gondwe left behind her mobile phone, a trail of questions, and the bank's employees in a panic, but one thing she didn’t leave behind was a trace. After the search started, it was revealed that just a few weeks earlier, Gondwe had paid her sisters and dependents rent ten months in advance before committing the crime. There have been rumours and whispers of sightings in Greece and Turkey, but none have been verified. Even now, five years later, with her image plastered on Interpol's Red Alert List of Most Wanted Criminals, Pamela is still on the run.

The Failed Indo Bank Robbery

If Pamela Gondwe is a masterclass on how to pull off a crime successfully, the following case is an example of what not to do.

Picture this: you’ve assembled a gang, set up a plan, and armed yourselves with a range of weapons from pistols to machetes. There’s only one problem: when you arrive at the bank, you discover the key to the vault is not held on the property. You have tied up a security guard for nothing, and instead of getting away with the hundreds of thousands you imagined, you pilfered two cellphones, a couple of laptops, and a getaway car from the staff.

This was the case at an Indo Bank in 2024 in the town of Lundazi. Worse still, both the vehicle and cell phones were recovered (still in Lundazi). One of the suspects (a police officer) was arrested in the town, and three others (as well as one of the stolen laptops) were arrested in Malawi with Zambian police uniforms.

Only one suspect is still on the run.

In the end, Zambia’s most memorable bank heists haven’t been the stuff of Hollywood — no high-speed chases, no intricate blueprints, no masked masterminds rappelling through skylights. What they’ve consisted of instead is a pattern of inside jobs, organisations being infiltrated with the use of a uniform, whether it’s that of the banks or the police. If crime truly doesn’t pay, then perhaps the lesson isn’t just for the thieves — but for the institutions that keep leaving the door, quite literally, ajar.