Let's delve into the lives of house caretakers, families who trade security for shelter in perpetually incomplete homes, trapped by a system where building their own house is a distant dream.

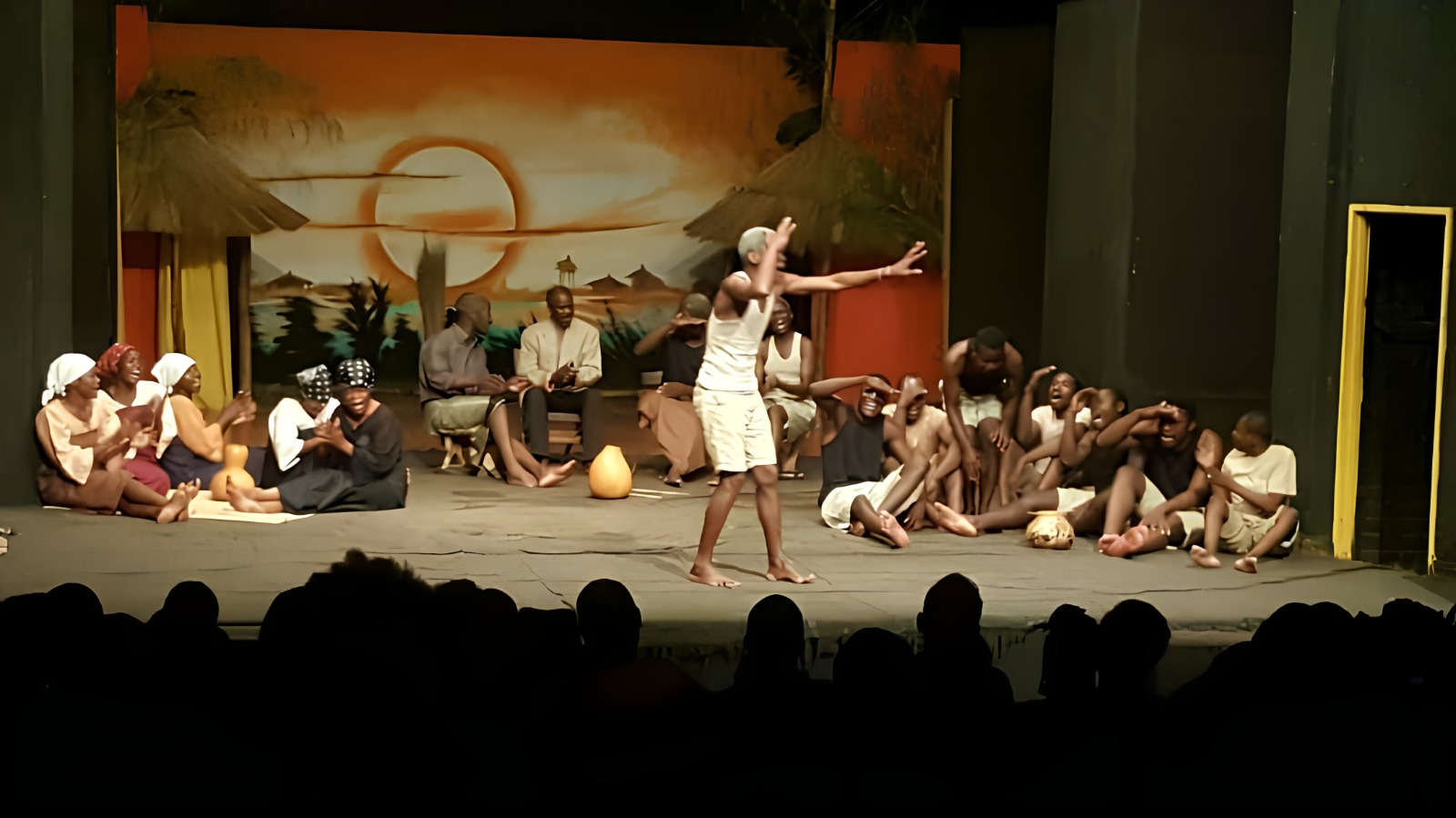

As you move through a neighbourhood marked by gates and fences, some houses stand out. These are homes with roofs but unpainted, sometimes unplastered walls, their bricks exposed. Plastic sheets or cardboard cover the windows, while chitenges or mealie meal sacks are draped over burglar doors. They harbour families acting as informal security and caretakers, who move from one unfinished house to another as their work concludes. This everyday reality reflects the nation’s broader housing and land issues, connecting individual survival with systemic shortages.

Who Are the House Caretakers?

For those living in rural areas, building a house is a financial strain. Families with nowhere to stay tend to temporarily occupy houses still in the process of development. “My brother allows me to stay here so I look after the house,” a caretaker tells me when I ask him how he found himself living in an unfinished house. “My brother still needs to find materials to finish the inside, so until then, I’m here.”

His payment for staying is to occupy the place, yet that stay turns permanent as saving to build his own house is overcome by the need to purchase daily needs. I asked him where he planned to build his own home, “I don’t know, maybe a farm, but that’s risky; buying from a headman is better.” Certain farmers designate a part of their land to those willing to buy it, but that doesn’t come with a title deed. If the farm has a new owner, they may want to evict those on their land. “It’s the same thing with a headman, you don’t get a title deed, yes, a farmer is riskier but also easier as you don’t go through a lot of politics.” The houses that the caretakers try to build are constructed with substandard materials and lack basic amenities.

Zambia's 1.5 Million Housing Unit Deficit

Housing for citizens in the urban and rural areas faces a deficit of 1.5 million housing units (2025). Reasons for this deficit include:

- Housing affordability: The cheapest house is equivalent to 25 years of an average urban household’s salary. Out of reach for the majority of the population.

- Population growth: There has been a rapid increase in population in informal settlements since the 2000s, tripling to almost 1.4 million people in 2020. That has led to a high density in population, with 148 people per hectare compared to the city’s 95 per hectare. The demand for housing has surpassed the supply of it.

- Policies and laws: The 1996 National Housing Policy gave confidence in a progressive Zambia, but a lack of financing and a proper implementation strategy stalled the process. That made affordable construction difficult, and the bygone colonial era building standards are not enforced on informal settlements.

- Infrastructure: Services such as water, electricity, and sanitation make formal housing unaffordable. Health problems increase due to the lack of proper drainage systems in informal housing and inadequate waste management.

Rural areas do not produce high income for the residents, so they migrate to cities such as Lusaka with the hope of finding high-paying work. This tends to cause a rise in the population of the city, which exceeds the housing supply. When the caretakers have nowhere to go, they are placed in Lusaka’s informal areas, where 70% of the city’s population resides. If your funds can’t build a house in a rural area, you can’t build a house in the city. A lack of a proper strategy that addresses poverty and provides proper finance and infrastructure in both rural and urban areas will prolong the problem.

Title Deeds and Risk in Zambia

The National Housing Authority needs to provide low-cost housing, but is hindered by a lack of funding. The country's regime has acknowledged the housing deficit and has taken steps to address the issue by initiating the Kwatuli Hills housing project. The goal of the project is to develop 220,000 housing units, and the government is working with the Zambia National Building Society to give citizens access to lenient land payments and financing.

Caretakers and their move to informal settlements is not a personal failure. As a community, valuing their role and addressing the underlying causes through strategic planning are vital steps toward sustainable housing solutions.