Tusona, the ideographic drawings of the Chokwe, embody Africa’s overlooked intellectual heritage. Once dismissed as decorative, these intricate line designs reveal advanced mathematical concepts such as symmetry, recursion, and algorithms. Used for teaching, storytelling, and philosophy, tusona demonstrates that African societies embedded complex knowledge systems long before Western science acknowledged them. Though impermanent in sand and ritual, they survive on artefacts scattered in European museums. Today, initiatives like the Women’s History Museum of Zambia seek to repatriate and restore their meaning digitally. Tusona offers not nostalgia, but a living code with the power to shape education, culture, and modern thought.

I am a Zambian woman, and here are two facts about me:

Firstly, I struggle with mathematics. Not in the adorable manner that gets a Disney princess saved, but in the sort of way that breaks a sweat at the sight of spreadsheets and quietly sidesteps careers in STEM. My saving grace is that I’m brilliant with money. At birthday dinners, I am an absolute joy at bill time. I de-escalate drama by calculating a fair tip without pulling out a phone calculator. I even include that one person who expects to escape the service charge because they only ‘had one Sprite’.

Despite my aversion, maths is everywhere. It is quiet and inescapable. It’s in the engineering that keeps bridges standing, in the rhythm of rainfall, in the flight paths of planes and birds. Whether we understand it or not, we live by its logic.

Back in the early 2000s, a public health campaign against HIV carried a powerful slogan: “You can’t tell by looking”. It was direct and chilling—a reminder that someone could appear perfectly healthy whilst carrying something hidden and life-altering. The message worked because it forced us to confront the limits of what we can see. That’s why I’ve always been uncomfortable with the idea that “if you can’t see it, it doesn’t exist.”

African culture has long known this truth. Proverbs like the Bemba saying, Ing’anda ushilala baikumbwa umutenge (you can only admire the roof of a house you don’t live in), prompt us to look beyond the surface. They challenge the gaze, encourage deeper seeing, and reward those who investigate the unseen: a wisdom that reveals hidden knowledge systems embedded in our heritage.

The second fact about me is that I do not have any tattoos.

Tattoos say something. I always wanted to stay safe and escape the judgments of those who may see them. Tattoos are enduring reminders of a person’s identity and beliefs. I told myself that I feared a tattoo on my bicep would droop to my elbow with age, that I would move on from that one particular Bible verse, or that I would run out of skin to name all the people I have loved. Though I still love my mother and recite Romans 8:37, I am a changing being.

Deep down, I fear the permanent foreshadowing of physical, public declarations. There is nothing I believe in strongly enough to place on my body. Nothing has defined my past, present, and future in such a permanent way.

But permanence does not only live in ink. Africa has always found permanence in knowledge systems etched into memory and ritual. In my search for permanence, I found tusona.

When it comes to African intellectual heritage, there is no shortage of it. The adinkra, a visual writing system of the Akan people of Ghana, and the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt serve as evidence of African intellectual systems and beliefs that were held as permanent. I looked closer to home and discovered tusona: visual, brilliant, complex, mathematical, and deeply philosophical images that drifted from daily knowledge in some parts of Zambia into oblivion.

“The line begins at a single dot and spirals outward, embracing all points without lifting from the sand.”

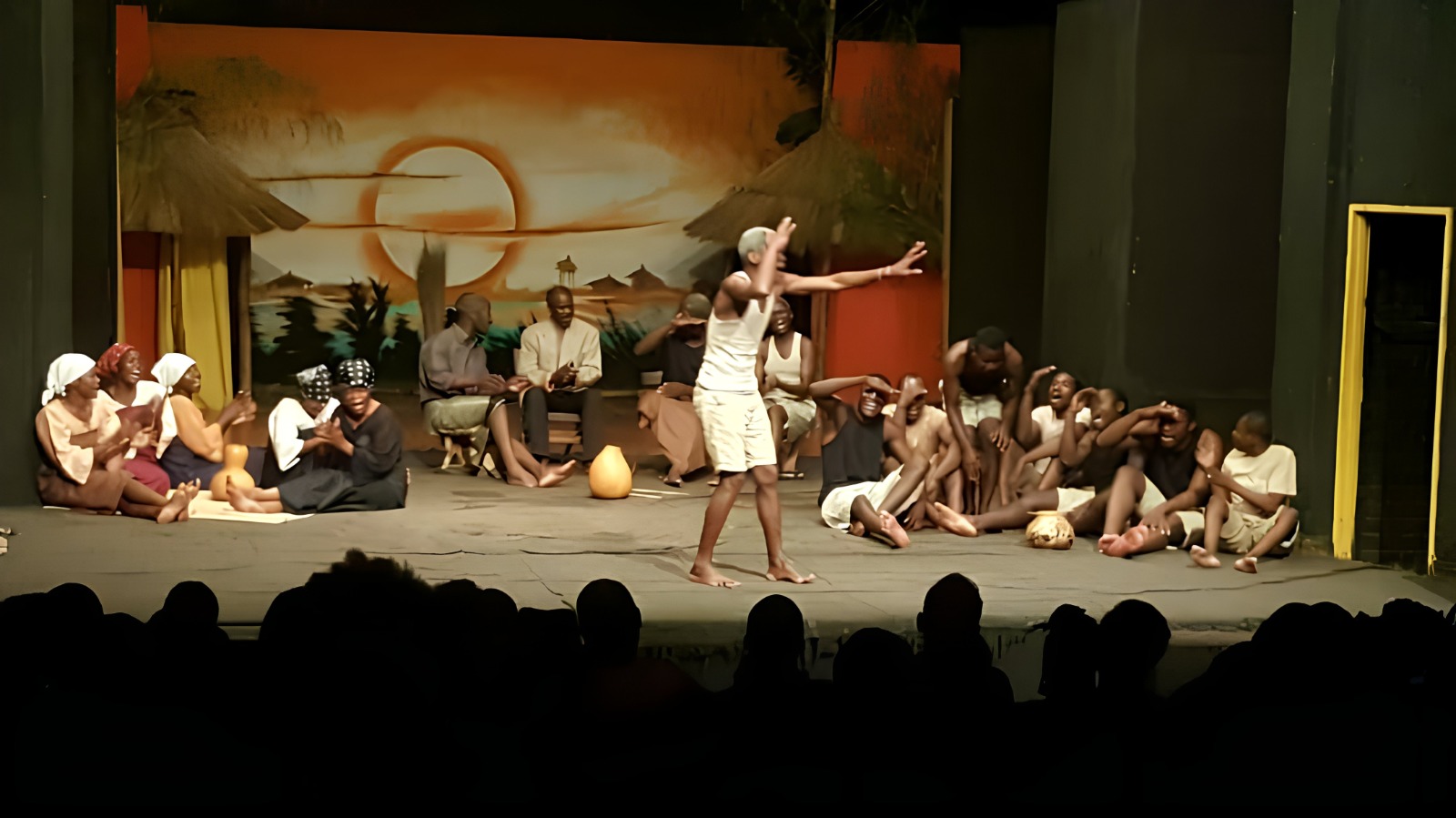

Tusona—to some, lusona, to others, sona elsewhere — are symbolic, ancient ideographic knowledge systems developed by the Chokwe people in parts of northeastern Angola, northwestern Zambia, and southern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Its earliest forms predate colonisation and were used not only as artistic expressions but as systems of education, storytelling, memory, and logic, traditionally written on smoothed-out ground with the fingertips. Akwa kuta sona, the writer, would narrate and teach proverbs, encode wisdom, tell stories, and pass on values, like a single continuous line weaving around a grid of dots, forming elaborate patterns and symmetrical designs.

Tusona is not only a visual mnemonic device; it is cognitive. Each design conveys layers of meaning that only initiated members can fully interpret. Like African proverbs, their truths were embedded beneath the surface, awaiting those trained to see.

In the early 20th century, tusona were recorded by missionaries and ethnographers working in Angola, though often within broader studies that did not always recognise their intellectual depth. It wasn’t until the late 20th century that their mathematical sophistication gained recognition, thanks largely to Paulus Gerdes, a mathematician renowned for his work in ethnomathematics across Africa.

Gerdes published scholarly works, including Lusona: Geometrical Recreations of Africa (1986), which mathematically decoded how akwa kuta sona used logical procedures to generate complex patterns. In other words, they can be understood in algorithmic terms, which are a precursor to step-by-step procedures resembling algorithms, long before computers were imagined.

One such early observer was Emil Pearson, a missionary who translated the New Testament into Luchazi and who documented tusona among the vaNgangela of present-day Angola. He described the process with vivid detail: “The index finger and the ring finger are used simultaneously. After the first two dots have been made, the index finger is placed in the hollow made by the ring finger, and the latter makes a third dot… This is repeated until the row is completed… When the dotting is completed, the real drawing begins. Using the index finger, the artist draws the lines and curves with a sure hand and without hesitation until the figure is complete.”

“Two paths interweave, never touching yet never separating, like the dialogue between earth and sky.”

What Western scholars would later call algorithms, the Chokwe people had long embedded in dust, geometry, and ritual. Their designs are not only mathematical; they are philosophies, whispered into patterns.

Some tusona reflect rotational and reflective symmetry, topological transformations, arithmetic operations, and recursive logic. They demonstrate understanding of the Earth and its elements. Tusona is mathematical literacy in a form unrecognised by Western epistemologies. It is one of many examples that demonstrate African indigenous mathematical thought, which existed long before Western academic systems arrived.

Tusona often follows mathematical rules: Gerdes noted that around 80% of the designs are symmetric and about 60% can be traced with a single, unbroken line. To create them, the writer began with a grid of dots and used step-by-step writing algorithms. The most common was the “plaited-mat” method, which guided the line around dots in a regular pattern. They also applied chaining rules that kept the line continuous and elimination rules that prevented overlaps.

Remarkably, they knew that if the grid’s sides were numbers that shared no common factors—like 3 x 5—the result would always be a one-line drawing. Ethnographers found that three-quarters of such “relatively prime” grids appear in surviving tusona, evidence that the tradition was not only artistic but also geometric, discovered long before it was written down.

Because tusona are impermanent through their medium of drawing into dust, they defied the colonial gaze. Europeans sought permanence in stone or ink, so tusona were dismissed as decorative rather than intellectual. Mainstream classification systems didn’t categorise tusona as “writing” or “science”, despite their function.

The paradox of invisibility is that it does not equal absence. Tusona were never truly lost like stars that only appear when the sun sets; their brilliance remains, waiting for us to see it.

The Women’s History Museum of Zambia is reclaiming silenced stories and artefacts by digitally repatriating Zambia’s lost material culture—artefacts from the 18th to early 20th centuries, including ceremonial leather cloaks, beaded relics, and geometric etchings linked to tusona.

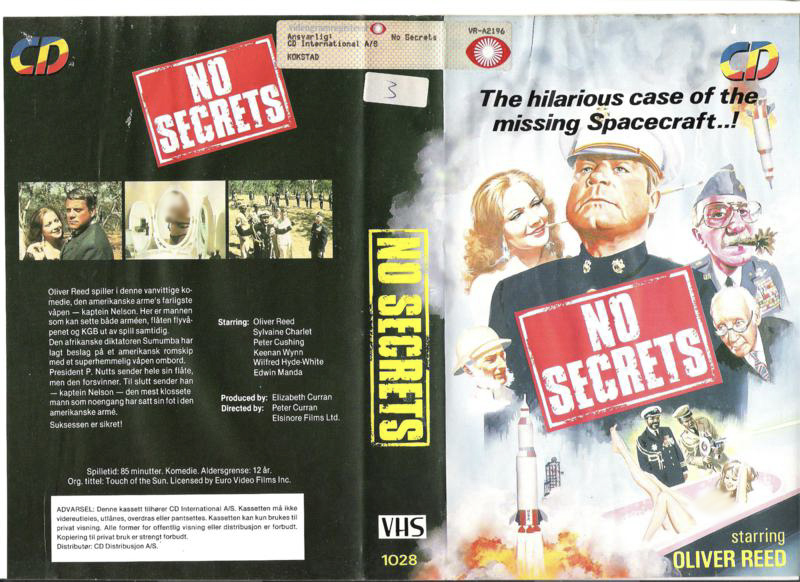

Today, tusona are not commonly taught in Zambian or Angolan schools. But tusona can be found on ceremonial cloaks, wooden stools, carved toolboxes, and dance masks housed in museums across Sweden, Germany, and Portugal. While not every motif is explicitly tusona, they reflect the geometric aesthetic of Chokwe culture.

“We’ve grown up being told that Africans didn’t know how to read and write. But we had our own way of writing and transmitting knowledge that has been completely sidelined and overlooked,” says Samba Yonga.

Their initiatives, including Shared Histories and The Frame, work with institutions in Sweden to trace provenance, recover knowledge, and reinsert Zambian voices into their artefacts.

“Taking into account the histories of women radically changes the perspectives of society. If we root ourselves in this history, we can draw from it a vision of bold possibilities,” notes Mulenga Kapwepwe.

“The pattern completes itself, the ending meeting the beginning, all dots connected in one unbroken truth.”

To carry tusona forward is not only to remember but to reimagine. It asks us to believe that our heritage is not a relic, but a living code capable of shaping the future.

We live under the rule of algorithms. Our job prospects are filtered through aptitude tests. Engagement formulas shape our timelines. Our purchases are predicted, our behaviours modelled.

We are part of systems we rarely question. I wonder what would change if Google’s neural networks were trained on African logic systems. Tusona is an ancestral algorithms that hold ancient reasoning, sequencing, and symbolism in our collective DNA. Tusona is a logic system and code that has existed outside the gaze of standardisation bodies like ISO, the International Standardisation Organisation.

Tusona has the potential to be integrated into formal education, as well as art, science, and philosophy. They can harmonise with modern tools and help reshape the questions we ask and how we answer them. While tusona artefacts may not return physically, we can clothe ourselves in the knowledge.

We can learn the language of their geometric designs. We can study the patterns, remember the heart of their initiation ceremonies, and share the stories with our children not as relics but as resources. Maths is not a stranger. It has been here all along, in tusona: waiting to be recognised, integrated, and evolved. Our ancestors embedded mathematical thought long before Western schooling systems asked us to “find x.”

I feared permanence, but now I dream of a sona-filled city where our Chokwe ideograms appear in highway codes that inform traffic signs, and architecture follows the curves and loops of tusona. I dream of young Zambians learning geometry with a grandmother’s finger in the sand, drawing a fable about creation.

This dream asks for participation, not waiting. It is not the work of scholars alone but of each of us willing to see and carry what is ours.

This stays a dream until I do my part. With that said, I’ve signed up for a maths course. And I’m getting a sona tattoo.