In Zambia, a funeral is a community event, not a private affair. Tradition roots in collective labour and support, seen vividly in villages, a modern shift in urban areas, where this open-door policy is sometimes exploited by individuals more focused on personal gain than genuine mourning.

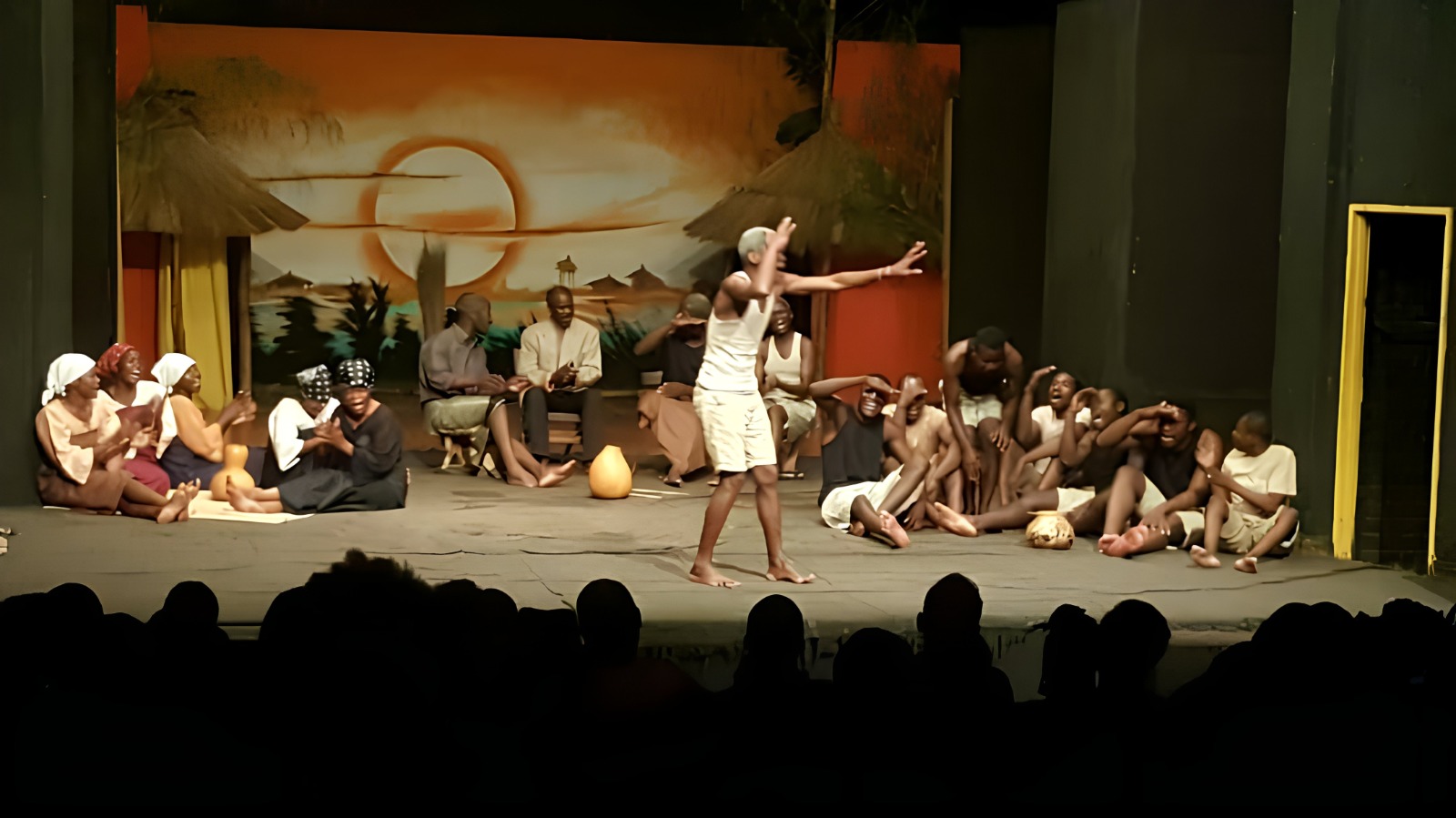

In Zambia, a funeral is not by invitation. It never has been. The door of the funeral house opens with the first cry of loss, and from that moment, people begin to arrive: neighbours, friends, distant relatives, and those who simply heard. In the Tonga villages scattered across the southern plains, these mourners come not only with their condolences but with their own provisions: mealie meal carried in sacks, chickens tucked under arms, a goat tied at the ankles and dragged along the dusty path. Grief here is collective, but so too is the labour of sustaining it. Even in the midst of mourning, the bereaved are spared the additional weight of feeding the many who come to grieve beside them.

How Zambian Funerals Embrace a Community

In Zambia’s cities, the same sense of duty still calls people together, but the rhythm has changed. The crowds now arrive in cars that choke the driveways and spill into the streets. Inside, the house fills quickly - sofas, reed mats, stools, and floors all occupied. Some bring offerings of cooking oil, mealie meal, or cash. Some bring nothing at all. Some were close to the deceased and shared a genuine ache. Others come merely to be seen. And from among those who arrive for reasons other than grief, emerge stories that were once rare but are now told with weary regularity.

I have heard of mourners standing up mid-service, leaving the family behind as the casket was lowered into the ground, all to secure a better place in the lunch queue. I have heard of others slipping Tupperware and takeaway containers into handbags to ensure there would be food to take home. And I have watched, over time, this quiet shift from funerals as sacred moments of farewell, to gatherings where, for some, the question is no longer how to say goodbye, but what might be gained before they go.

The Changing Urban Funeral

No matter how accustomed we become to grief, it is one of those things that feels new each time it arrives. There is no playbook, no amount of experience that can soften its blow. The newly bereaved often have to set aside their pain to endure the exhausting process of arranging a funeral. Proper grieving becomes something postponed, a task for later.

They are pulled into a whirlwind of logistics: tents to hire, programs to design, meals to prepare. And layered atop all this are the expectations of certain mourners who treat funerals less as solemn farewells and more as social events, akin to weddings or birthdays, where their enjoyment, whether through food, drink, or comfort, takes precedence over the family’s raw and aching need to mourn.

Historically, the reason for the open-door policy at Zambian funerals was rooted in the belief that death was something that affected the entire community, and that the only way to pull through was through the strength that comes with numbers. With numbers came hands to stir the nshima, to console the bereaved, to take over household chores, and to assist with burial arrangements. Back then, it was more widely understood that the intention of grieving with the family was not to walk away with more, but to lighten their load.

A point of praise for Zambian culture has always been its openness. The fact that an invitation is never needed, the door is always open, and people are guaranteed to be fed. It is considered un-African to be inhospitable. However, when we parrot our traditions without understanding the wisdom and reasoning behind them, they risk becoming something to be exploited for individual gain. Struggles, distortions, and perversions are bound to arise when we try to maintain traditions conceived in a collectivist culture, while many Zambians, through colonisation, have adopted an increasingly individualistic mindset. In practice, this means that customs meant to strengthen community ties, like shared meals, mutual support, and collective responsibility, can sometimes be reduced to mere rituals, stripped of their original purpose.

The true spirit of these traditions can only endure if we reconnect them to the values of care, reciprocity, and shared humanity from which they emerged. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that these traditions are often more fully understood and honoured in rural communities, such as Tonga villages, than in the bustle of the city. There, daily life remains closely woven into communal practices, and people grow up participating in, observing, and inheriting the meanings behind these rituals.

The Weight of Logistics

When this is neglected, we risk the very thing we are seeing more and more of in our funeral culture today. This leads to an approach to being hosted that is so ignorant of the tradition's purpose, it becomes thoroughly uncultured and inconsiderate, while justifying its existence through the shield of tradition, and if this continues, we risk the doors of the funeral house being closed completely.

If we are to keep our traditions alive, we must do more than perform them. For the sake of both our culture, the people lost and what more we stand to lose when we disrespect the very real process of grieving. Being present, be thoughtful, be generous - these are the true measures of culture, far beyond the rituals themselves. The future of our community depends not on blind adherence to tradition, but on understanding why these customs exist and choosing to honour them with intention. And treating our bereaved with the same comfort and care we would expect from others at our most vulnerable time.